When the economic headwinds start blowing, the first reaction of most businesses is to examine marketing budgets and ‘trim the fat’ where possible. On the surface it makes sense. Spending less on advertising means less expenses on the balance sheet and less waste.

And this is true in a sense. It is impossible to advertise without a percentage of waste, regardless of how detailed your buyer personas or how narrow your targeting is. So cutting advertising spend reduces the amount of ‘wasted’ dollars.

However, lurking beneath the surface of this seemingly rational decision are very important business costs that cutting advertising spend will have on your business:

- A (likely) sudden and dramatic drop in sales.

- Investment required to re-grow the brand.

- The opportunity cost to grow share of voice (and gifting the opportunity to competitors).

- Decline in sales.

Advertising is brand oxygen. Without it, not enough people know about you. And if they don’t know about you, they can’t buy your products or services. When advertising spend is cut, the brand loses the ability to influence purchases, whether directly via performance marketing or indirectly through brand marketing. And so sales decline.

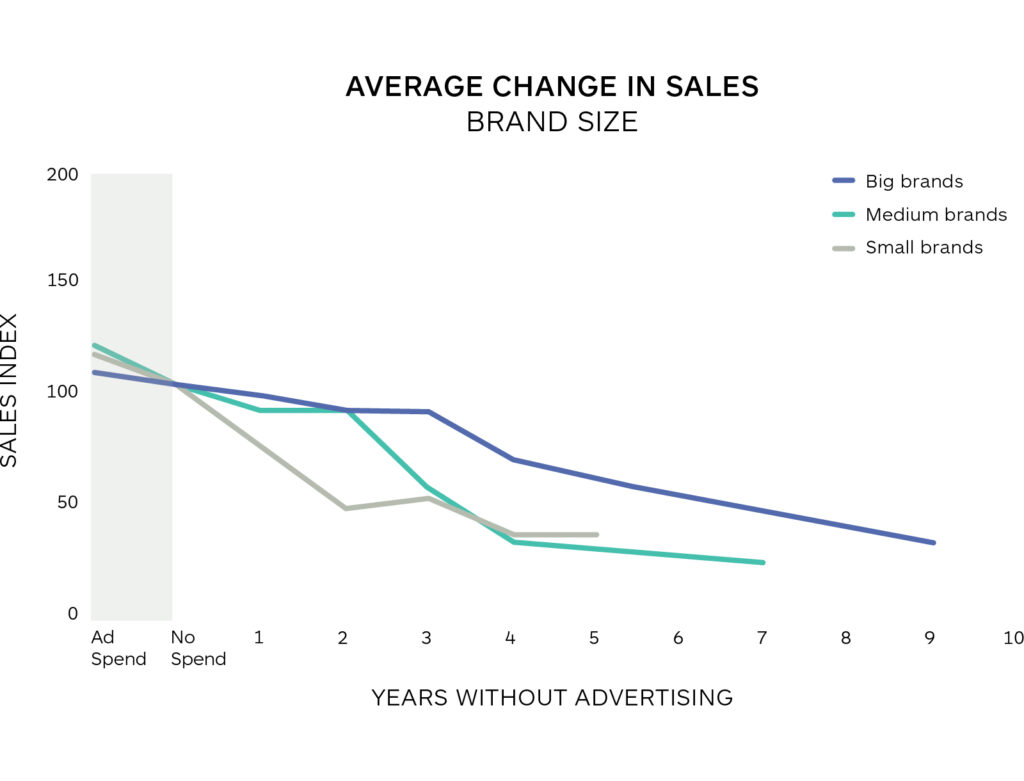

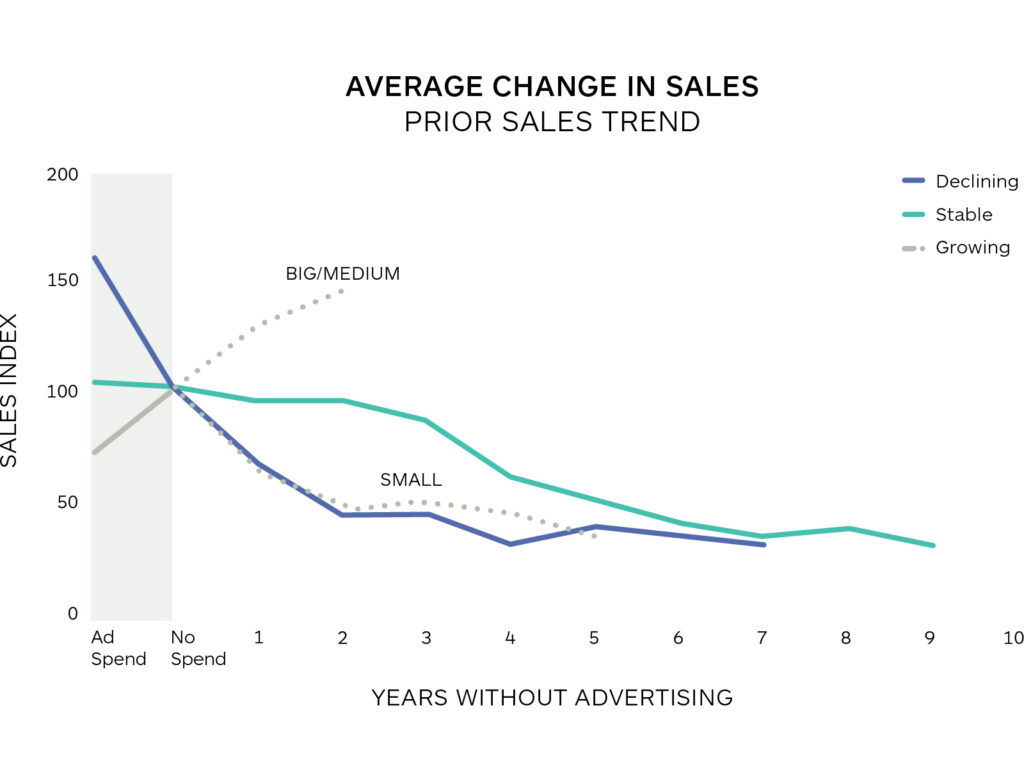

Research suggests that the rate at which this occurs differs depending on two important factors:

- The size of the brand (small/medium/large).

- The performance of the brand prior to cutting off advertising spend (growing/stable/declining).

The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute conducted a study of 70 competitive brands in Australia for over 20 years. They observed 57 cases where a brand cut all mass media advertising for a year or longer.

Key findings of the study include:

- Average 16% decline in sales for all brands in Year 1. This increased to 25% in Year 2, and 36% in Year 3.

- The effect is most pronounced for small brands, with the decline immediate and sharp.

- Large brands maintained a high level of sales for 1-2 years before declining. This is hypothesised to be due to a high level of physical availability (e.g. store distribution and shelf placement) acting as a purchase cue.

- Already declining brands declined faster.

- Small brands, regardless of prior performance, declined immediately.

- Medium/large growing brands continued to grow.

It is also important to note that these results were when mass media advertising (TV, radio etc.) with a less direct impact on buyer behaviour, was cut. If this study were to be replicated with performance marketing, it is very likely that these results would be far more severe.

In any case, the evidence is clear. Cut your advertising spend and you will reduce your sales.

The long road back

If advertising is brand oxygen, as we’ve detailed above, then we can turn the supply back on and start drawing some deep breaths straight away … right?

All we’d need to do is turn those paused ads back on and sales will resume as though nothing has ever happened. After all, we know how the ads perform and, most likely, our audience hasn’t changed (much).

Again, the research doesn’t agree with this commonly held assumption.

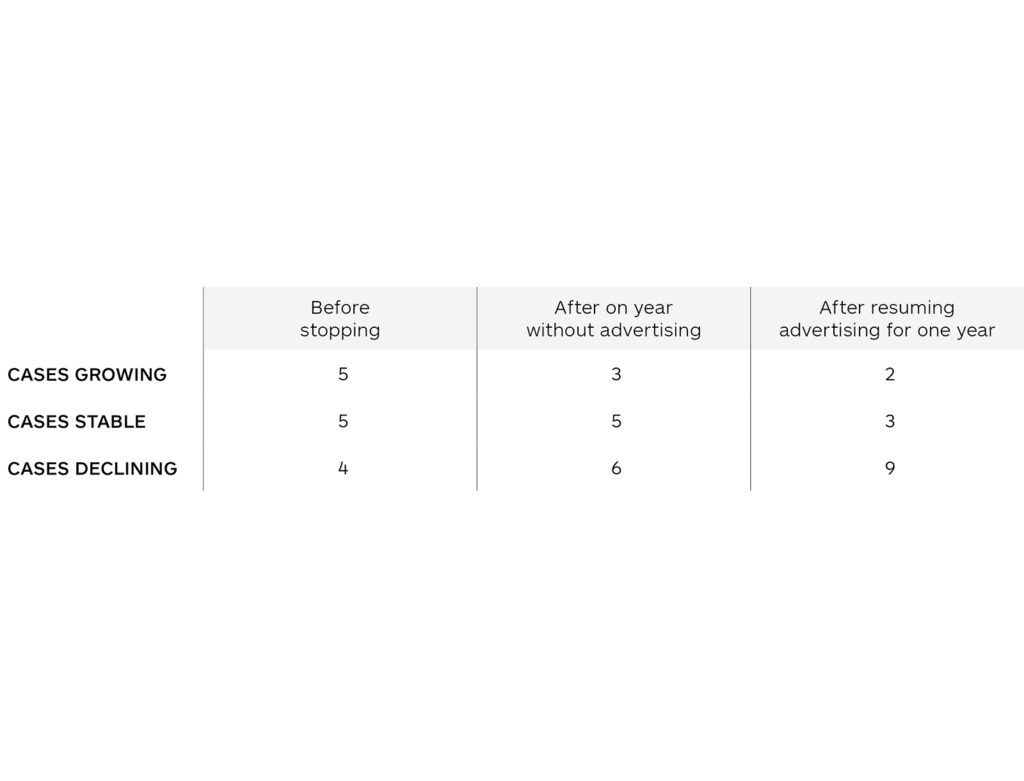

As part of the same study, the Ehrenberg Bass Institute also examined 14 cases where a brand stopped advertising for one year and then resumed the following year. Although a small sample size, the results are very interesting:

After stopping spend and resuming:

- More brands declined.

- Less brands remained stable.

- Less brands grew.

The lesson is very important: it takes longer than a year of advertising to make up for a hiatus of one year. But why is this?

Fundamentally, marketing is about influencing buying behaviour and the ‘driver’ of buying behaviour is the brain of our buyers. It is the job of marketers to influence the thoughts and feelings of our buyers. But that’s not an easy prospect. It takes repeated exposure and consistency over a long period of time to exert any level of influence over buyers and advertising is the most effective way of achieving this on scale.

When we stop advertising, people think less often about the brand and the existing thoughts and feelings customers have about our brands begin to fade from their memory. In a practical sense, it means their feelings and opinions towards the brand weaken. Brands that previously sparked feelings of joy, now flicker and fade to dreaded indifference. Strongly held opinions fade to obscurity, or worse, become mistakenly attributed to a more active brand. This means that when we re-ignite our advertising efforts, we are first faced with the challenge of re-building decayed memories of our brand before we can generate any behaviour change.

This takes time and considerable financial investment to achieve, and all of the dollars invested in doing this are extra costs the business faces as a result of cutting advertising spend in the first place. And that’s not to mention the lost sales during that time either.

Missed opportunities (or gifting opportunities to your competitors)

At the onset of Covid, the World Economic Forum calculated that total investment in advertising decreased by 10% in the US, and 12% in the UK during the first half of 2020. By Q2, the Interactive Advertising Bureau reporting 24% of brands completely paused all advertising activity.

It’s a response repeated time and time again, across all industries, through the typical cycles of the market.

History tells us that when this happens, there are two opportunities for brands that remain in market:

- Advertising costs less.

- Share of voice increases.

The cost of advertising is influenced by supply and demand. Less competition (i.e. advertising demand) means you pay less to achieve the same results. This factor is compounded by the opportunity less advertising competition presents.

With less competitors competing with you for the attention of your customers, your share of voice grows by simply maintaining advertising spend.

Importantly, Binet & Fields (2013) have proved that a sustained share of voice growth is linked with long term market share growth – so the benefits of extra share of voice are connected to the bottom line of your business. Essentially, your ability to influence buying behaviour has been boosted by competitors withdrawing from the competition.

In the worst of the 2020 pandemic months, this scenario was played out by the two great brand rivals, Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

Coca-Cola cut back on advertising investment by 35% (roughly $3.5billion in budget). Their CEO at the time James Quincey stating: “Why would I want to spend money in a period if I can’t get the return, particularly if there’s a strong lockdown? We thought, no marketing is going to make much of a difference in the second quarter, so we pulled back heavily.”

Arch-rival PepsiCo, by contrast, maintained their ad spend throughout this period.

The results? Coca-Cola reported a net reduction in revenue of 11%, while PepsiCo seized the opportunity presented to them and reported net revenue growth of 5%, just by simply maintaining spend.

This example also demonstrates the duality of this competitive circumstance.

Not only is your brand passing up the opportunity to grow share of voice through down markets, cutting advertising expenses is also conceding this opportunity to your competitors.

With your brand out of their way, they are free to dominate the share of voice and capture the minds of your customers in your absence. All you can do is hope they don’t seize the opportunity you’ve gifted them.

So, what are you really saving?

Yes, cutting advertising spend reduces the marketing expense. But it comes at a considerable cost to the business. Failing to properly recognise these costs is a flawed decision-making process that jeopardises the long-term health of your brand (and bottom line).

At best, the cost of cutting advertising will be a decline in sales and the missed opportunity for brand growth. At worst, your brand will concede market to your competitors and be forced to play the expensive, and resource-draining game of catch-up for years to come.

If you need marketing advice or would like to grow your business, contact the team at IvyStreet here.